NIMBY and the Data Center: Lessons From the Battle of NewarkNIMBY and the Data Center: Lessons From the Battle of Newark

When you announce your next project, will it be greeted with praise or protest? A recent controversy surrounding a project in Newark, Delaware offers lessons for data center developers.

July 22, 2014

When you announce your next project, will it be greeted with praise or protest? That's an important question for data center developers in the wake of the collapse of a controversial project in Delaware.

On July 10 the University of Delaware terminated its lease with The Data Centers LLC, which had planned to build a large data center supported by a 279-megawatt energy generation facility featuring combined heat and power (CHP) that would allow it to operate "off the grid." It was heralded as a forward-looking data center cogeneration project that would bring jobs and up to $1 billion in investment to the town of Newark.

The project was met with resistance by members of the local community, which coalesced into Newark Residents Against the Power Plant, a grass-roots group that made masterful use of social media to drive an alternate narrative: that the power plant was a threat, and developers were hiding critical facts about their plan. This scrutiny was a major factor in the university's decision to back out of the project.

Lessons for future projects

It would be easy for the industry to view the "Battle of Newark" as an isolated incident involving a unique project, with limited relevance to other developments. But data center developers should pay close attention, as the Delaware debate introduced a new scenario: the data center as a political hot potato.

It's instructive to examine the tactics adopted by NRAPP in mobilizing opposition to The Data Centers' project:

The group quickly deployed a web site and built a following through an e-newsletter, Facebook and Twitter.

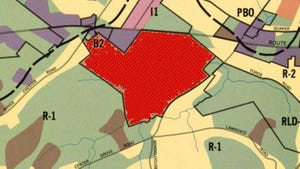

NRAPP tracked every development on its web site and social channels, posting 150 documents, hours of videos of local meetings and maps of the data center site and the surrounding neighborhood.

It assigned "neighborhood captains" to distribute yard signs, T-shirts and door hangers and hand out flyers and fact sheets about the project.

The group mobilized support from other organizations, including the Delaware Audubon Society, The Sierra Club, student groups, university faculty, the Delaware Coalition for Open Government and various environmental groups.

NRAPP tapped the skills of professionals in its membership, using the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) to gain access to documents, and filing a Superior Court lawsuit to oppose the project.

"We have proven that the very concept of the 'done deal' is now dead," the group said in a statement. "The community’s voice is powerful in shaping our future. The significance of this effort extends beyond the power plant and will have a positive impact on our community for years to come. It also serves as a powerful example for other communities facing similar challenges."

That last sentence is worth considering, as NRAPP has created a template for future efforts to mobilize opposition to data center projects. So how do developers avoid a protracted battle over future projects? There are several "lessons learned" from the Newark fiasco they should keep in mind.

'Power plants' are problematic

Data centers don't usually freak people out. But power plants do.

There haven't been many NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) disputes about data centers. Staffing is minimal, so they don't place a burden on local traffic or schools. Noise and emissions can usually be contained on site. These projects boost the tax base and are seen as symbols of the new economy. That's why many data center builds are announced by the governor at a press conference.

But when a power plant wants to move into the neighborhood, it can prompt a very different reaction. The on-site power project developed by The Data Centers was innovative for the data center industry. It's fair to say that the developers expected their project to be welcomed as a data center. But the neighbors looked at the plans and saw a power plant.

This is a power-obsessed industry. On-site power is being included in more and more data centers, albeit rarely at the scale attempted in Newark. Large banks of diesel backup generators sometimes attract scrutiny, as was the case in Quincy, Washington. But this equipment is well known and understood by most homeowners.

Developers implementing new approaches to on-site power generation would do well to either build in remote areas or be prepared to take time to explain the technology to local officials and residents. Which brings us to our next "lesson learned."

Communication is critical

The Newark project was plagued by credibility issues in the developers' communications with the community. Problems arose almost immediately after the project's announcement in May 2013. A month later, The Data Centers met with representatives of the environmental group The Sierra Club, seeking their endorsement. The outcome was exactly the opposite.

"Once we realized the nature of the plan, we let them know we would not 'endorse' a power plant and immediately set about to let neighbors in Newark know of the plan," the group said. A non-disclosure agreement between The Data Centers and the city of Newark quickly became a trust-killer for residents, who were left with the impression that developers and local officials had something to hide. Residents reached out to news media to air their grievances, and NRAPP launched the website to publicize its grievances.

When The Data Centers held its first public meeting in early September, it drew 400 attendees and generated a lengthy list of questions from residents, who cited concerns about potential emissions and pollution, the impact of new natural gas lines and the impact on a residential neighborhood near the property.

In short, the project's opponents defined the narrative early on, and the developers never recovered. The Data Centers rarely addressed the issues on their web site, and don't appear to ever have used Twitter or Facebook to communicate their side of the story.

"We've done a poor job of verbalizing this project," said Gene Kern, president and CEO of The Data Centers, in an interview with NewsWorks. "It's very hard to explain to people how we will operate this facility because we haven't actually done it and we don't know our (electrical) load requirements, so we can't communicate it exactly."

Strategies for the 21st century

The Data Centers was clearly taken by surprise by the fervent opposition of NRAPP and its skill in community organizing. Nothing like this had been seen before in the data center industry. That won't be the case the next time a controversy arises.

That's why data center developers would do well to adopt communications strategies that work in 2014. These should include:

A realistic assessment of a project's potential for controversy.

A plan for educating local officials and residents about the data center and its components (including on-site power).

Early outreach to key stakeholders and making executives available for dialogue with the community.

A "rapid response" capability to address concerns and media coverage.

Active social media channels that allow the company to speak directly to constituents and stakeholders.

Not every data center project is right for every community. When neighbors have questions, they deserve answers that address their concerns. At the same time, the conversation should be based on facts, not speculation. Good planning and effective use of communications tools can ensure that a project gets a fair hearing, and the community has a chance to make a fully informed decision about the proposal.

Even if a project is rejected in one site, it could find new life somewhere else. A week before the university announced the lease termination, The Data Centers said it was exploring other potential sites for its project. Meanwhile, officials in Kent County, Delaware, are already holding discussions with the developer.

About the Author

You May Also Like