Post-Heartbleed, Data Centers May be Better Prepared

Heartbleed was a rude awakening for data center managers two years ago, but waking up and facing the problem has actually been beneficial.

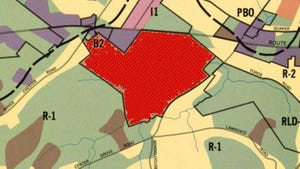

In retrospect, the vulnerability classified as CVE-2014-0160, whose discoverers dubbed “Heartbleed” and rendered a logo for it, was not all that devastating. The true danger came as a result of the discovery itself: a portion of OpenSSL encryption code that was left unchecked since having been finalized in January 2011.

Now that nearly two years have passed since local TV newscasts first misrepresented Heartbleed as a “virus” and caused more mass hysteria than any other software bug, history may end up recording its existence as a net benefit for data centers.

“Heartbleed has not only given the [OpenSSL] project a kick in the pants, and a renewed focus, it actually led to a regeneration and rebirth,” said Tim Hudson, who co-founded the OpenSSL Project (originally called SSLeay) back in 1996. “We’ve also noticed that security researchers have been much more active.” Hudson is currently CTO of security consultancy Cryptsoft.

Higher Priorities

One of the biggest unresolved problems faced by data centers and their tenants was the low priority that company executives placed on researching and implementing the solutions to vulnerabilities. Although OpenSSL was among the most open of open source code, both the severity and the obscurity of the open hole in its code were due, in large part, to lack of interest.

Hudson believes giving the vulnerability an identity beyond “CVE-2014-0160” thrust it in the face of executives who would otherwise have ignored it. But Heartbleed also created a new and positive trend, he believes: Researchers now have both the incentive and the financial backing — including in the form of outright grants, said Hudson — to dive deep into the oldest and coldest code, in a concerted effort to thwart any likelihood of a sequel.

“The renewed focus in security research is working to help improve the (vulnerability) database,” he told attendees at the RSA 2016 security conference in early March. “The more people looking at the code, the better that the code is going to get.”

As a result, the process of perfecting the core infrastructure code of data centers is finding a rhythm, and becoming somewhat more automated than it was. What’s more, commercial developers and security interests are paying more than just attention to the integrity of infrastructure code, said Hudson. Underwriters also came to the realization that each Heartbleed sequel would have a potential for costing organizations more than its predecessor.

“The amount of testing that’s being done on the OpenSSL code base, post-Heartbleed, is many orders of magnitude higher than pre-Heartbleed,” said Hudson. “And that is a good thing. If we’d gone out as a project team and said, ‘Hey, can somebody help us do more testing?’ Silence. Crickets.”

Now, the possibility of discovering — and perhaps laying claim to — the sequel, increases the potential that research teams can get more funding. The motivation is greater now that organizations — their executives in particular — have a quantifiable interest in ensuring that “the next Heartbleed” doesn’t impact them.

False Comfort

There remains, however, a lingering threat: After outsourcing some or all of their data center resources to cloud service providers, some organizations may be comforting themselves with the belief that their IT assets are automatically secured.

That threat was brought to the surface during the first day of the RSA conference, by a symposium of the Cloud Security Alliance. There, Raj Samani, vice president and CTO for Intel Security in the EMEA region, told CSA members he’s encountered situations where municipal service providers, such as water companies, are being assured that the threats imposed by such factors as unchecked software vulnerabilities, subside once they’ve moved to the cloud.

An exploit for an unpatched OpenSSL vulnerability, even to this day, could lead to what Samani calls “integrity-based attacks.”

“Today, there are companies right now offering water treatment applications... through cloud computing,” said Samani. “Now, when I looked at the security of this particular service, they said, ‘You don’t need to worry about antivirus updates, because they're stored in the cloud.’ That’s funny, right? Until you realize that the company that’s keeping the water clean for your local area is using that provider.”

Granted, Heartbleed was not a virus. However, the whole Heartbleed escapade made clear that, at the executive level, too many organizations believed that security vigilance can be accomplished through periodic “cleanings” of the system — manual labor-like tasks that can be outsourced to service providers.

There are some major service providers that would be happy to take their business. In March, the Global Services unit of British telco BT entered into a partnership with Intel Security (parent company of McAfee), in the interest of renewing an effort to share real-time indicators of possible threats to data centers — stopping exploits, including to municipal infrastructure and citizen services, before they spread.

Brian Fite, senior cyber physical consultant with BT Global Services, believes such real-time indicators will be more valuable to organizations in the long run than continuing to trust the good intentions of open source foundations.

“Anybody’s who’s actually helping the trustworthiness of shared code repositories, is (doing) a good thing,” said Fite. “With OpenSSL, we all kinda trusted it because it was open source, but what were we basing that trust on? In hindsight, probably fairly flimsy indicators.”

BT Americas’ CTO for its security consultancy practice, Konstantinos Karagiannis, added to Fite’s point that the best intentions of open source contributors doesn’t amount to much when a corporation makes a risk assessment for its critical IT infrastructure.

“I love open source. But a serious problem is that some of the most important packages in Linux are being maintained by one person at a time, maybe two. That’s a serious flaw. The ‘many-eyes’ theory that you hear about, for open source? Sometimes those eyes are two.”

HPE’s CTO for security software, Steve Dyer, repeated that warning during an RSA session.

“With the old idea that ‘all eyes make all things shallow’ — one of the mantras of open source in the beginning — you’d think would extend to security,” said Dyer. “That hasn’t exactly proven to be true. What it may be is, ‘all eyes’ give the bad guys enough time to look at code, and really figure out what’s vulnerable about it.”

Dyer believes that many applications are comprised of mashups of open source components. “In my mind, that actually amps up the need for us to keep an eye on open source.”

That “eye” to which Dyer refers includes automated tools, such as HPE’s own Fortify, to scan open source code in addition to original code. The results of HPE’s own open source scans, he said, are contributed back to the developer community.

The Path Forward

The solution BT’s Karagiannis suggested, however, is precisely one Cryptsoft’s Hudson says he’s seeing more of: investments by organizations of their developers’ time and resources to contributions to the maintenance of critical code.

“If you’re saving millions of dollars a year because you’re using a bunch of open source packages, maybe it’s not the worst karmic thing in the universe to have a few developers spend two weeks in the summer, helping out with one of those packages that you make so much money off of.”

When asked if he was confident that no part of the world’s data center infrastructure would need to be subject to the same level of humiliation that OpenSSL was subjected to, Hudson responded, “Absolutely, this will happen again. “There are a pile of critical infrastructure projects that are under-resourced, and it’s the work and passion of one or two individuals. Effectively, they’re a Heartbleed waiting to happen.

“What we’ve done as a project team is, the dirty laundry is all out there in the open. We want people to learn from our experiences,” he continued, “to reduce the likelihood. But it will not be possible to eliminate.”

About the Author

You May Also Like