US Intelligence Got the Wrong Cyber BearUS Intelligence Got the Wrong Cyber Bear

Why the "Russian hacking" story in the US has gone too far

January 3, 2017

(Bloomberg View) -- The "Russian hacking" story in the U.S. has gone too far. That it's not based on any solid public evidence, and that reports of it are often so overblown as to miss the mark, is only a problem to those who worry about disinformation campaigns, propaganda and journalistic standards -- a small segment of the general public. But the recent U.S. government report that purports to substantiate technical details of recent hacks by Russian intelligence is off the mark and has the potential to do real damage to far more people and organizations.

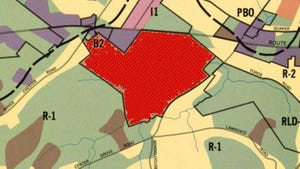

The joint report by the Department of Homeland Security and the Federal Bureau of Investigation has a catchy name for "Russian malicious cyber activity" -- Grizzly Steppe -- and creates infinite opportunities for false flag operations that the U.S. government all but promises to attribute to Russia.

The report's goal is not to provide evidence of, say, Russian tampering with the U.S. presidential election, but ostensibly to enable U.S. organizations to detect Russian cyber-intelligence efforts and report incidents related to it to the U.S. government. It's supposed to tell network administrators what to look for. To that end, the report contains a specific YARA rule -- a bit of code used for identifying a malware sample. The rule identifies software called the PAS Tool PHP Web Kit. Some inquisitive security researchers have googled the kit and found it easy to download from the profexer.name website. It was no longer available on Monday, but researchers at Feejit, the developer of WordPress security plugin Wordfence, took some screenshots of the site, which proudly declared the product was made in Ukraine.

That, of course, isn't necessarily to be believed -- anyone can be from anywhere on the internet. The apparent developer of the malware is active on a Russian-language hacking forum under the nickname Profexer. He has advertised PAS, a free program, and thanked donors who have contributed anywhere from a few dollars to a few hundred. The program is a so-called web shell -- something a hacker will install on an infiltrated server to make file stealing and further hacking look legit. There are plenty of these in existence, and PAS is pretty common -- "used by hundreds if not thousands of hackers, mostly associated with Russia, but also throughout the rest of the world (judging by hacker forum posts)," Robert Graham of Errata Security wrote in a blog post last week.

The version of PAS identified in the U.S. government report is several versions behind the current one.

"One might reasonably expect Russian intelligence operatives to develop their own tools or at least use current malicious tools from outside sources," wrote Mark Maunder of Wordfence.

Again, that's not necessarily a reasonable expectation. Any hacker, whether associated with Russian intelligence or not, can use any tools he or she might find convenient, including an old version of a free, Ukrainian-developed program. Even Xagent, a backdoor firmly associated with attacks by a hacker group linked to Russian intelligence -- the one known as Advanced Persistent Threat 28 or Fancy Bear -- could be used by pretty much anyone with the technical knowledge to do so. In October 2016, the cybersecurity firm ESET published a report claiming it had been able to retrieve the entire source code of that malicious software. If ESET could obtain it, others could have done it, too.

Now that the U.S. government has firmly linked PAS to Russian government-sponsored hackers, it's an invitation for any small-time malicious actor to use it (or Xagent, also mentioned in the DHS-FBI report) and pass off any mischief as Russian intelligence activity. The U.S. government didn't help things by publishing a list of IP addresses associated with Russian attacks. Most of them have no obvious link to Russia, and a number are exit nodes on the anonymous Tor network, part of the infrastructure of the Dark Web. Anyone, anywhere could have used them.

Microsoft Word is a U.S.-developed piece of software. Yet anyone can be found using it, even -- gasp -- a Russian intelligence operative! In the same way, a U.S.-based hacker aiming to get some passwords and credit card numbers or seeking bragging rights could use any piece of freely available malware, including Russian- and Ukrainian-developed products.

The confusion has already begun. Last Saturday, The Washington Post reported that "a code associated with the Russian hacking operation dubbed Grizzly Steppe" was found on a computer at a Vermont utility, setting off a series of forceful comments by politicians about Russians trying to hack the U.S. power grid. It soon emerged that the laptop hadn't been connected to the grid, but in any case, if PAS was the code found on it and duly reported to the government, it's overwhelmingly likely to be a false alarm. Thousands of individual hackers and groups routinely send out millions of spearphishing emails, meant for an unsuspecting person to click on a link and thus let hackers into his computer. Now, they have a strong incentive to use Russian-made backdoor software for U.S. targets.

For Russian intelligence operatives, this is an opportunity -- unless they're as lazy as the U.S. reports suggest. They, in turn, need to switch to malware developed by non-Russian-speaking software experts. Since their work tends to be attributed to the Russian government based on Russian-language comments in the code and other circumstantial evidence, and the cybersecurity community and the U.S. government are comfortable with the attribution, all they need is Chinese- or, say, German-language comments.

The U.S. intelligence community is making a spectacle of itself under political pressure from the outgoing administration and some Congress hawks. It ought to stop doing so. It's impossible to attribute hacker attacks on the basis of publicly available software and IP addresses used. Moreover, it's not even necessary: Organizations and private individuals should aim to prevent attacks, not to play blame games after the damage is done. The most useful part of the DHS-FBI report is, ironically, the most obvious and generic one -- the one dealing with mitigation strategies. It tells managers to keep software up to date, train staff in cybersecurity, restrict their administrative privileges, use strong anti-virus protections and firewall configurations. In most cases, that should keep out the Russians, the Chinese and homegrown hackers. U.S. Democrats would have benefited from this advice before they were hacked; it's sad that they either didn't get it from anyone or ignored it.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners. It also does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Data Center Knowledge and its owners.

About the Author

You May Also Like