Hyperscale Data Centers Under Fire in HollandHyperscale Data Centers Under Fire in Holland

The position of the government, however, is not as radical as it first appears.

February 7, 2022

The Dutch government is seeking to impose environmental controls on hyperscale data centers after declaring that their high energy demands outweigh any benefit they bring to the national economy and the lives of the country’s citizens.

Newly reformed after a crisis of public trust that caused its premature dissolution a year ago, the government told parliament that the policy was a response to protests and political opposition that flared last year over Facebook’s plans to build a giant data center outside Amsterdam.

At the time, the country’s leadership had been embroiled in talks to form a coalition government that were so difficult that they took longer than any others in Dutch history.

While Dutch politicians finally signed their coalition agreement on 13 December, environmental campaigners from Extinction Rebellion staged a protest at local government offices in Zeewolde, where councilors where preparing to vote on whether to approve Facebook's giant data center.

The decision-making was so fraught that it caused a split in one of the ruling political factions, preventing the local Green party from fielding candidates in upcoming local elections and thus denying them seats in power for the next four years.

The faction that formed in their wake was pro-development and pro-Facebook; Zeewolde council greenlit Facebook's plans, as the nation watched on the news. Vocal opposition continues ahead of local elections in March – an event coinciding with a public consultation that will ultimately decide, barring any legal challenges, whether the data center is approved.

Amidst the controversy, the four main Dutch political parties now agree that "hyperscale data centers make disproportionate demands on our sustainable energy supply, relative to their social and/or economic benefits."

The new government would therefore "tighten up" national regulation of data centers and criteria that govern how civil planners weigh their decisions to approve them.

Meanwhile, opponents of the Facebook project have passed a motion in the Dutch parliament to effectively ban the construction of hyperscale data centers until the government formulates a national data center policy. Facebook's data center in Zeewolde would make such great demands for energy, farmland, and water, they said, that it would be "contrary to the public interest." The government is not obliged to comply. And its position is not as radical, or as confident, as it first appears.

Playing politics

The government had no evidence to support its assertion that the environmental costs of hyperscale data centers outweighed their social and economic benefits, a spokesman for the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate told Data Center Knowledge.

"There is no concrete plan behind it. The agreement is a very short statement that all the parties could agree on. Typically, we would have a plan behind it, with context. But because of the way this coalition came about, there's agreement on all the points that all these plans have yet to be developed," he said.

The Dutch government did intend to publish a national data center policy, but its scope is unclear.

In a customary statement to parliament in January, the minister for Climate and Energy said every matter concerning data centers was still being decided.

Data centers housed nearly ten times as much computing power in 2020 than they did a decade ago, and carried fifteen times more Internet traffic, yet they consumed almost the same amount of electricity, the International Energy Agency said in November. The reason was growing numbers of hyperscale data centers, and advances in computer hardware and software. Hyperscale data centers were typically more efficient than other computing facilities. The cloud computing companies that ran them, along with other computing and telecoms firms, accounted for half the global spending on renewable energy in the last five years.

Activists and some politicians in Zeewolde and the Dutch parliament have been arguing variously that hyperscale data centers used renewable energy that could be reserved for other industries. Such data centers brought no social or economic benefits to local people, they said, in circulars distributed through Facebook.

"The company does not provide essential digital services. Meta does not take the facts, the privacy of people and democracy of countries seriously. And it uses our online interaction as a source of income to influence our behaviour. Such a company is not an asset to the Netherlands but a blot on our society," proclaimed one Extinction Rebellion campaign.

They were also indignant that public officials had for two years conspired with Facebook – albeit legally – to obscure its name from local democratic proceedings and official documents concerning its planning application. Politicians and locals have protested the erection of three large Google and Microsoft data centers elsewhere in the country.

Facebook parent Meta told Data Center Knowledge by email that its data centers were among the most energy-efficient in the world, and ran entirely on renewable energy. In Europe, the company sourced energy from wind farms in Norway and Holland.

To date, Meta said it bought 7 gigawatts of renewable electricity to run its data centers worldwide. Dutch public records show that this would equal about one third of all energy Holland expects to produce from a host of large North Sea Wind farms it aims to build by 2030.

Support and opposition

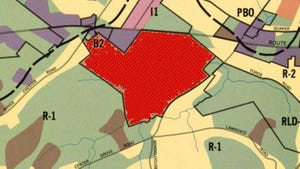

Zeewolde municipality, a new-town area outside Amsterdam built on Flevoland – a land reclaimed from the sea in the 1960s and earmarked for spillover housing, farmland, and more recently, wind farms, light industry, and data centers – merged Meta's poject into a planned business park expansion. The site would cover 356 hectares, with 166 hectares of it (almost half, and as much as about 232 football pitches) consumed by Facebook's data center campus. Activists were alarmed by its size – it was as big as Holland's three existing hyperscale data centers combined.

Officials in Zeewolde told Data Center Knowledge most of the businesses on their industrial estate were logistics firms. One reason they welcomed Facebook was that it would future-proof and diversify the region’s economy and workforce.

"Lots of large companies don't use green energy, but Meta does,” said Renate Slokker, company contact officer at Zeewolde municipality, who is working on the data center development.

"We can't live without data centers. We talk to each other with WhatsApp and Instagram and Facebook. But we don't want them in our back yard? It's NIMBY behavior."

"Our national railway company uses much more electricity than a data center. But nobody is against our national transport by rail,", Hans Polet, location advisor at Zeewolde, told Data Center Knowledge.

"Zeewolde has enough electricity for these big companies. We can send the data centers to an East European country and then they are not going to use green electricity. So they better be in the Netherlands."

A few years ago, the government of Amsterdam, one of the world's largest digital infrastructure hubs, said that by 2030 it would have no more room for new data centers, nor the electricity to power them. National planners and regional authorities reckoned Flevoland, and in particular Zeewolde and neighboring Almere, were best equipped to support the industry as it continued to grow. The required grid expansion would moreover accord with regional plans to build housing and industry.

Erik Barentsen, senior policy officer at the Dutch Data Center Association, said there were no technical obstacles to meeting the data center industry's demand for power. The only obstacle was political.

Holland was concerned about revelations last year that it was failing to meet its environmental targets to cut greenhouse emissions. It was trying to prevent traditional industries from using fossil fuels and had committed to eliminating gas power entirely. Growing electricity consumption and fear that the electrical grid would not support it had become sensitive political issues.

Barentsen said concern about the energy consumption of data centers had consequently been blown out of proportion, and made it into the coalition agreement.

Data centers consumed relatively little energy compared to other industries in Holland, he said – about three percent of the total in 2020.

"That's not huge right? That doesn't make a big difference, let's be honest. It's good that there's been discussion about this. But it's not an objective discussion anymore. It's very subjective. We need a national strategy for data centers, otherwise we will have these discussions all the time."

About the Author

You May Also Like