Exchanges to New Jersey: Tax Trades, and We’ll Move Data CentersExchanges to New Jersey: Tax Trades, and We’ll Move Data Centers

NYSE, Nasdaq, Cboe threaten to leave the state if the new proposal to tax electronic trades is passed.

If you’ve paid attention to the business of high-frequency trading infrastructure in recent years (and no-one will judge you if you haven’t), Friday’s news of New York’s exchanges threatening to move out of New Jersey data centers may give you a sense of Déjà vu.

Threatening to leave the state if it imposed a new tax on trades was a tactic CME Group’s executive chairman, Terry Duffy, used in 2016, when Illinois wanted to start charging $1 or $2 per trade executed on exchanges in the state.

Now, NYSE and other exchanges that host matching engines in New Jersey data centers are using the same tactic to fight a new state proposal to tax electronic trades. Like other states, New Jersey has a massive gap in the state budget caused by the pandemic-induced economic crisis, and its legislators are looking for every possible way to close it.

Equinix, which operates a New Jersey data center that’s become a trading hub, has also joined the “coalition” of companies protesting the bill, Bloomberg reported. So have market makers Citadel Securities and Virtu Financial. The proposal would put a tax of one-fourth of a penny on every electronic transaction processed in the state by any company processing at least 10,000 transactions a year.

State Assemblyman John McKeon, a Democrat and the tax bill’s lead sponsor, thinks the state should be paid for having been “blessed to have the geography that is able to serve [the function of being home to electronic trading engines] for the financial markets… ,” according to The Wall Street Journal. (The “blessing” appears to be the fact that New Jersey is physically close to Wall Street but much cheaper – and safer – to operate in than Manhattan.)

Needless to say, exchange operators disagree.

On Friday The Journal and Reuters both reported having obtained copies of an internal NYSE memo that announced plans for a week-long test starting at the end of the month, in which one of its exchanges (NYSE Chicago, the smallest of the five) will run out of a backup data center in Chicago instead of the primary one in Jersey.

NYSE isn’t alone, according to the memo, which reportedly described “an industrywide effort in which US exchanges will test their backup sites in the Midwest on Sept. 26, a Saturday when the market is closed,” wrote The Journal.

Nasdaq said it will simulate a regular trading day on that date, using its backup data center in Chicago as the primary site running its matching engines for equities and options, Bloomberg reported. Citing notices they sent to clients, Bloomberg said Nasdaq and Cboe “emphasized the importance of the test to ensure markets were ready to relocate.”

Their concern is easy to understand from a business perspective – if not from the perspective of a business in a position to help a state struggling amid a crisis of historic proportions. Making trades more expensive to execute would cut into their profit margins and could theoretically lead to traders executing fewer trades, resulting in less revenue for the operators in the long term.

Had the exchanges actually gone through with what the memo implies they are threatening they could do, the impact would go far beyond trading. While NYSE operates its own data centers, much of the trading ecosystem that has grown in New Jersey lives in colocation data centers, whose operators charge a premium for space near the trading engines and the opportunity to interconnect and become part of the ecosystem.

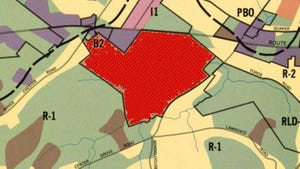

One of the densest nerve centers of this ecosystem is Equinix’s NY4 data center in Secaucus, which explains the colocation company’s decision to join the coalition against the proposed tax. If the exchanges moved elsewhere, so would a good chunk of the state’s data center services market.

At a press conference Friday New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy said the state’s dialogue with the industry had just begun, and that the tax wasn’t imminent, according to Bloomberg. The proposed tax would be temporary, to tide the state over as it struggles through the financial crisis, he said. (“It’s not a forever thing.”)

But in August Murphy also cautioned against relying on any potential new tax on electronic trades for closing the state budget gap, since exchanges would likely try to overturn any such law in court.

Suing would be plan B. Plan A for the exchanges appears to be building negotiating leverage by demonstrating that they can shift platforms out of state without great disruption. How effective the tactic will be remains to be seen.

While it’s unclear how much Terry Duffy’s threat to move CME’s trading engines out of Illinois had to do with it, the 2015 trading tax proposal went nowhere. But these are very different times.

Read more about:

EquinixAbout the Author

You May Also Like