Cloud Server Provider Linode Adds Second Tokyo Facility

Citing a surge in Asia/Pacific customer activity, especially from both Japan and China, virtual cloud and Web hosting provider Linode announced Monday it’s adding a second data center facility in Tokyo. And in the wake of another round of denial-of-service attacks targeting its Atlanta facility last September, on top of a significant round of attacks the previous December, Linode told Data Center Knowledge it is committing to switch the hypervisors hosting new virtual server instances from Xen to KVM, beginning with the opening of the Tokyo 2 facility.

“We were the target of some DDoS attacks earlier this year, and the Tokyo 2 transit configuration implements many safeguards which prevent or reduce the impact of attacks,” said Brett Kaplan, Linode’s data center operations manager, in a message to Data Center Knowledge Tuesday. “The amount of bandwidth we have now gives us headroom for when we are attacked again. We also have multiple diverse transit providers which can help in the event of DDoS attacks, congestion, and cable cuts.”

In an indication of having seriously reconsidered its architecture to thwart new attacks — which Kaplan clearly accepts as a fact of life — Linode will no longer be offering Xen hypervisors as the controllers for its new servers. While KVM has been an option for most customers, up until this week, customers in Japan did not have the option of moving their Linode instances from Xen to KVM. They may now take advantage of that option, Kaplan told us, by migrating their instances to Tokyo 2. As incentive, Linode is offering RAM size upgrades for customers who make the shift.

Strategic Shift

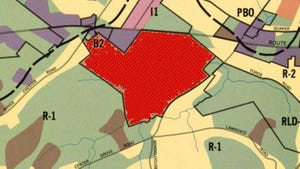

Linode will be renting this space from Equinix, the provider told us Wednesday. It’s promising better connectivity for this new facility, blending multiple transit providers — including NTT, Tata Communications, and PCCW — with settlement-free peers such as Japan’s BBIX exchange.

“With Tokyo 2, we have implemented a very robust transit platform,” Kaplan told us. “This gives us more bandwidth than we had at our Tokyo 1 facility while providing the same latency to countries in the region.

“We also have additional redundancy in the form of diverse transit providers. Should one transit provider go down or become too congested, we can route to one of our other providers. We have also built in plenty of headroom so we can easily add more bandwidth and transit providers down the line. . . One of the most important aspects of this project was to ensure that the new facility not only supports the high-density power standard we require, but also gives us plenty of room to grow from a space, power, and cooling perspective for many years to come. I can confidently say that Tokyo 2 meets all of those requirements.”

Linode’s business model is simplified. It offers four basic types of virtual server instances for consumers, distinguished mainly by their memory sizes — 2 GB, 4 GB, 8 GB, and 12 GB. Compute cores, storage, and bandwidth are proportionately bundled in with all of these instance types. It charges flat, hourly rates of 1.5¢, 3¢, 6¢, and 12¢ per hour, respectively. Then it proceeds to larger instance types all the way to 120 GB — suitable for very large, in-memory databases — at $1.44 per hour.

Response and Resolve

When it suffered under the weight of DDoS attacks last year, to its credit, Linode was unusually transparent and forthcoming about the preventative measures it took, including why some of those measures failed. For example, network engineer Alex Forster explained the use of “blackholing” as a method of discontinuing the use of specific IP addresses, in the event they’ve been targeted.

“Blackholing fails as an effective mitigator,” wrote Forster at the time, “under one obvious but important circumstance: when the IP that’s being targeted – say, some critical piece of infrastructure – can’t go offline without taking others down with it. Examples that usually come to mind are ‘servers of servers,’ like API endpoints or DNS servers, that make up the foundation of other infrastructure.”

As a result, he went on, it was particularly difficult for Linode to mitigate attacks against its servers, and the infrastructure provided to Linode by its colo providers.

With the target of those attacks arguably the network infrastructure, exactly what does changing the brand of hypervisor have to do with protecting against future attacks, or mitigating the effects of those attacks? On the surface, it seems like fortifying a city’s air defenses to protect against an attack from the sewers.

Yet there is precedent. In 2012, a research team with Canada’s Simon Fraser University studied the effects of a limited DDoS attack in a laboratory setting [PDF], using four different configurations of hypervisor, including both Xen and KVM. They discovered that virtual machines running on these various platforms had differing response profiles, when performing synthetic benchmark operations both in normal circumstances and under attack.

In fairness, Xen and KVM under-performed one another in different categories of the SFU tests. Yet it was clear that the researchers were capable of leveraging the open source nature of KVM, coupled with its unique architecture, to develop virtual I/O drivers that would at least attempt to mitigate the effects of overburdened traffic patterns.

We often talk about data center architectures needing to become adaptable to changing circumstances, and transparent about how they go about it. Perhaps we should count Linode as a case-in-point.

[This article reflects corrections to Linode's price plans.]

Read more about:

EquinixAbout the Author

You May Also Like